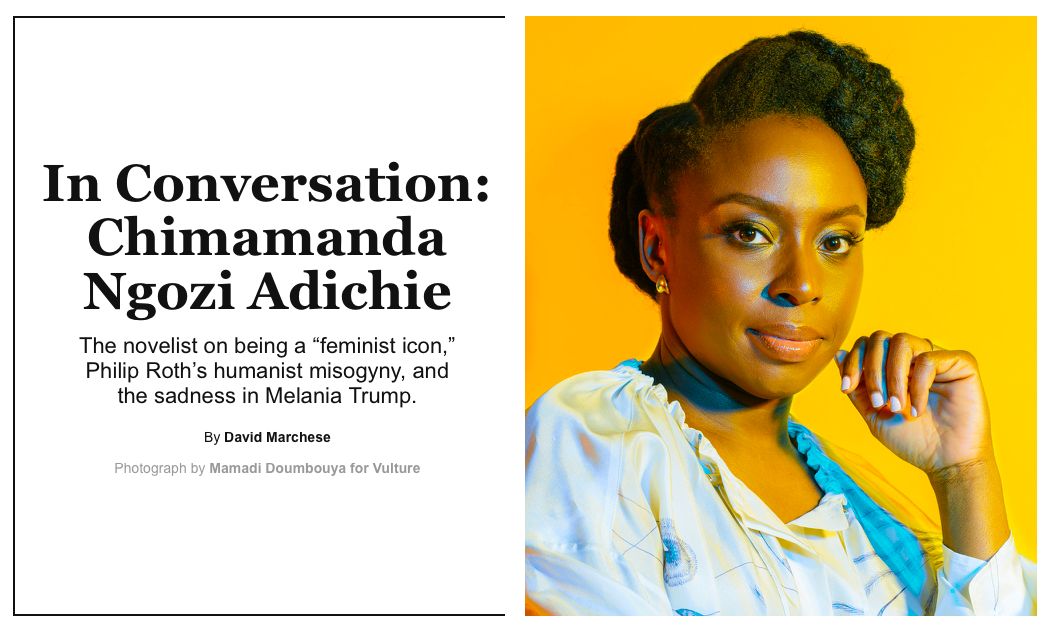

Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, in an interview with VULTURE in New York, gave a detailed perspective into a lot of issues going on in today’s world. The author opened up on rape, raising children, Melania Trump, empathy and a lot of other topics.

Read excerpts below.

On wanting to tell the truth: I want to tell the truth. That’s where my storytelling comes from. My feminism comes from somewhere else: acute dissatisfaction. I don’t remember a time when I didn’t want to tell stories. Sadly, I also don’t remember a time when I wasn’t telling people what I think about the world.

On thoughts about raising a boy: If I had a boy, one of the things I would do is not just say it’s okay to be vulnerable, but also to expect him to respect vulnerability. Actually, shaming him into vulnerability is a good idea, because there’s so much about the way that masculinity is constructed that’s about shame.

What if we switch that shame around? Instead of shaming boys for being vulnerable, why don’t we shame them for not being vulnerable? I kind of feel — I was going to say I feel sorry for men, but I don’t want to say that.

On #MeToo changing gender and power dynamics in meaningful ways: I hope it does, but it hasn’t. What I like about #MeToo is the idea that now women’s stories have the possibility of being believed, which is almost revolutionary. Now a woman can tell her story and she might still get castigated, but there’s the possibility that she gets public support and that there are consequences for whoever harassed or assaulted her.

That’s not happened before. But the shape of the narratives around #MeToo can still be troubling. It’s the idea that a woman doesn’t deserve sympathy unless she’s “good.” I’m sorry to get into race, but it’s similar to what happens with black men, where in this country it seems that they are not deserving of sympathy unless they are pure. If a young boy is murdered because he was going off to buy Skittles but we learn that he smoked marijuana, then that somehow makes him not deserving of sympathy.

He shouldn’t have to be perfect to deserve sympathy and that applies to women as well. And, also, the way women are cast as innocent or blameless or helpless undercuts the idea of female agency. Often we’ll say things like, “She was coerced into going to the guy’s apartment.”

On raising her daughter: I wrote that [Dear Ijeawele] when I wasn’t a mother and it’s easier to write about a hypothetical child than to write about a real one. The child that book was addressed to is sort of an idea of a child. But having my own — you don’t realize how difficult it is day-to-day to combat negative ideas. Sometimes when you’re raising a child it’s like the universe is in a conspiracy against you.

You go to the toy store looking for something not necessarily “girly” and you’re overwhelmed by the pink and the dolls. Even the prayers my daughter got from family members: They’re like, “We hope she finds a good husband.” I’m optimistic that those kinds of things will change but I think about how women are socialized — even the most resistant women still get things under our skin.

On male and female literary differences: There are many things that a famous male writer can do without worrying about the risk of not being taken seriously — if you’re interested in fashion, for example. Very often women writers have to tread much more carefully because their grip on being considered as serious — which has nothing to do with how the world is — is more tenuous.

When a woman says something controversial, she’s much more likely to be criticized about her personality and even about how she looks. Not that men don’t get that, but women get it more quickly and more often. And to be specific to writing, a man can write about a subject like marriage and immediately it can be seen as an insightful take on society. But a woman writes about marriage and it’s seen as this smaller, more intimate thing.

We’ve gone past the point where women are directly criticized for their subject matter, but the language used about their writing hasn’t really changed. When men and women write about similar things, what the women write is often cast in less lofty terms.

On her short story about Melania Trump: There’s a sense in which her characterization in the story still holds true for me. There’s something I feel about her and it lives in the same emotional space as compassion and pity — and that feeling has increased. Actually, when I wrote that story I thought it was about Trump’s daughter [Ivanka]. I saw the story as making a case for how he [President Trump] is unstable but is surrounded by people who are stable and reasonable, such as his daughter and his wife.

There was also a very feminist take to the story’s premise, which was that the women around him know what they’re dealing with. There’s a kind of knowingness in dealing with somebody they care about but understand is crazy. I’ve since changed my mind about his daughter.

On Melania Trump: I look at pictures of her and I see great sadness. I don’t want anyone to be sad, but the idea that she might be sad about her situation is almost comforting because it reminds you that there’s still some sort of humane presence in the private space of the White House.

On being seen as a “feminist icon”: When I started, all I wanted was to write books that somebody would read. I didn’t plan to become this “feminist icon, which is something I feel uncomfortable with. People say, “This is what you’re known for.” But that’s not what I know myself for.

On motherhood and her art: I used to think I wouldn’t be a good mother because I was so dedicated to my art. I said to myself, I have nephews and nieces who I adore, and I helped raise them, so those will be my children. That’s what I thought for a long time, because I felt that I couldn’t be true to both my art and my child. Getting older [changed that]. I like to joke and say that you’re ready [to have a child] when your body isn’t ready, and when your body is ready, you’re not mentally ready.

No comments